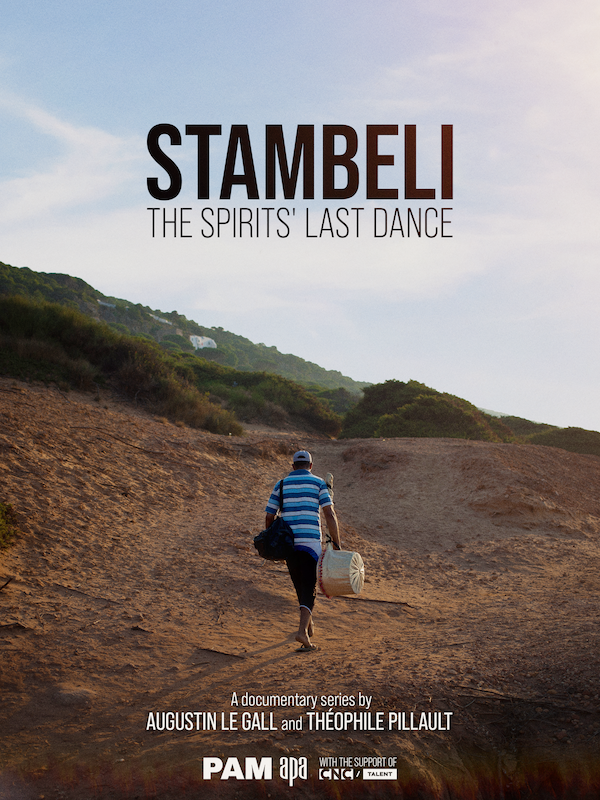

A long time ago, before Covid and the first lockdowns, journalist Theophile Pillault wrote an article for PAM dedicated to this ritual, illustrated by the superb images of the photographer Augustin Le Gall, who has been visiting communities of followers of this secret ritual, often confined to private homes or consecrated sanctuaries, for the past ten years. Augustin intended to continue the adventure with a documentary film, and Théophile proposed to extend it with an episode centered on the influence of Stambeli on a whole generation of electronic musicians fascinated by the hypnotic loops of its trance. This is how the first buds of this documentary triptych called Stambeli, the spirits’ last dance, were born. It is finally available, as of today, on PAM’s YouTube channel.

Music and spirits

To enter this universe, as mysterious as it is abundant, one needs keys. Augustin Le Gall found them, one day in 2008, in the person of Riadh Ezzawech, one of the last mediums (Arîfa) who facilitates the communication between the living and the spirits who seek to be incarnated. “I knew,” says the photographer and filmmaker, “that in the month of Sha’ban – the month before Ramadan – there were a lot of ceremonies, and when I met Riadh he was preparing his pre-Ramadan ritual in which he must call all the spirits he represents to attest to his rank and bless the community. Riadh is also the guardian of the sanctuary (zaouia) of Sidi Ali Lasmar, in the heart of the medina of Tunis, where a black saint, a freed former slave, is buried.”

For several years, Augustin frequented the zaouia, the ceremonies held there, and the healing rituals hidden in the heart of the private houses. It is also where he met Lotfi Karnef, whose family has long been linked to Stambeli. He chose to learn the gombri (or guembri), a three-stringed bass lute that, backed by chkacheks (metal castanets), gives the rite its rhythm, calling the spirits who start to dance. It is with this self-taught musician, who learned in the shadow of Riadh Ezzawech, that the first episode begins. His instrument and the role it plays in the ritual are the spotlight. “It is a music,” he explains, “that makes you vibrate from the inside. The low notes are the soul of the gombri, it resonates throughout your body.”

He whose parents are the guardians of the shrine of Sidi Saad, east of Tunis, also accompanies Riadh Ezzawech on a pilgrimage that the medium takes regularly to the cave of Sidi Ali El Mekki. It is dug in the rock, on the side of a mountain that rushes into the sea. A tongue of sand extends past it, escaping into the horizon, pointing to the Sun that fades into the waves. To reach it, Riadh and his family walk in procession, along the coast and close to the painful stories that once inhabited the place: not far from there, a port was used for the slave trade from sub-Saharan Africa. It is to them, in particular, that we owe the arrival of animist practices that took refuge in the shadow of the saints and the Muslim religion. The sea is also where spirits dwell, and so it is appropriate to pay homage, through songs, music, and appropriate sacrifices. This is what Riadh and his family do, and then, once they reach the sanctuary, the music launches an extraordinary sequence that shows the feverish beauty of the dance of the spirits that Riadh embodies, spinning in a breathless trance that gains in intensity as the gombri and the chkacheks redouble their fervor. Augustin, who had already explored the world of the Gnawas of Morocco, remembers the shock of discovering the Stambeli. “What attracted me was the question of the invisible, which exists through humans, ceremonies, dances… and how this invisible materializes. There is a staging of the arrival of the spirits – materialized by the changes of costumes, their objects, sometimes the throne that indicates their rank… Visually, it is very strong.” It’s impossible to put into words what was captured on film, (shot by Hazem Berrabah nad Mongi Aouinet) and in the edit of this sequence which, without trying to explain everything, immerses us in the ritual.

Who am I?

“Who am I? Am I Riadh, Am I Arîfa? God, guide me…” It is with these questions of Riadh Ezzawech that the first episode of the documentary ends. The second is centered around the medium and the sanctuary for which he is responsible: Sidi Ali Lasmar. It is said that at the time when the Ottoman Empire had its governors in North Africa (in the 18th and 19th centuries), one of them had granted the communities of Stambeli four houses dedicated to worship. Later, more would be listed, but at independence, the nationalist policy of President Habib Bourguiba, who sought to forge a unitary culture at the expense of identity-based particularisms, as well as the sale of a number of buildings belonging to the state – including the shrine where Riadh officiates, will weaken the cult, and with it a whole history and tradition. The second episode, entitled Inheritance, shows us Riadh’s struggle to keep the ritual alive, and to preserve the sanctuary, which the owner, who had bought it from the State, wants to sell, even if it means putting an end to its rich history. And at the same time, that which all these years gave meaning to Riadh’s life. For he did not choose to be the caretaker of Stambeli, it was the spirits that called him… at least that is how the mediums consulted at the time interpreted his illness, initiating him into his role as a medium capable of guiding, calming, and interpreting the wishes of these entities.

Riadh struggles to find a replacement: but what will happen if the ritual disappears, for lack of replacements: “it would be like a social death,” explains Augustin. Hence his question: “Who am I?” Who is Riadh if he is no longer Arîfa? Meditating on these ideas, Riadh adds, “a country without history is no country“. A concern that applies to Stambeli, as well as to other original traditions that history and a certain idea of modernity have gradually buried. Stambeli, explains Théophile Pillault, director of the third episode, “is an anchor of the Africanity of Tunisia. Ifriqiya is the old name of Tunisia, but the country has been confined to Arab visions, Mediterranean, Carthaginian … dialects and particularisms have been smoothed.” In the absence of new initiates, this African anchorage and its richness are exhumed by a generation of young artists that Stambeli inspires. In their own way, they rediscover it and offer it, through music, a new and unexpected life.

Electro-Stambeli, a musical rebirth

Théophile Pillault arrived in Tunisia for the first time in 2014, on the eve of the legislative elections that saw the victory of the Ennahdha party. Very quickly, he met DJs and electronic producers such as Deena Albdelwheb and the Arabstazy collective which includes Amine Metani, the main character of this third episode, Transmission. It is with them that he discovered “a very rich alternative and underground scene with hyper sharp vision, though certainly in a westernized microcosm… artists who have one foot in Tunisia and the other in France, who keep an ear on the English and French scenes, and at the same time who are Tunisian, Arab and African, and who have the heart to dig their heritage.“

In the documentary, we find Amine Metani as he goes to the Sailing Stones festival to perform, and he takes advantage of this stay in his native country to deepen his research on Stambeli. He visits Riadh, attends a conference of a Stambeli researcher, stops at Dar Barnou – another Stambeli house where he got his customized neo-gombri to be amplified and subjected to all the modulations that pedals and other mixing tables allow. Amine, co-founder of the Shouka label, is not a “practitioner” of Stambeli, but its universe inspires him. “It is a ritual that I personally feed into my work as a musician, in my own spirituality, but these are not communities to which I belong,” he explains to the camera. And in fact, he as well as some of his comrades, draw from the music of Stambeli the richness that blossoms in their synthetic sounds.

But the meaning goes beyond that. “I found it fascinating,” says Théophile Pillault, “to follow a guy like Amine who has a double culture, to see him walk a path of quest, of rediscovery of identity because it is also his country. It was exciting to see how a kid born in Tunisia, but who spends his life in France, returns to the country to rediscover something deep…” . And this is one of the basic questions that the documentary asks. Faced with the disappearance of such a rich tradition, is there in this re-appropriation by the younger generations a form, certainly, partial, of transmission, and perpetuation of its heritage? No doubt not as much as Riadh would hope, but nevertheless: “things are bound to disappear, to change, and today what young people do brings us together … we have moved the form – the Stambeli cures the problems of everyday life, and the music to take people out of their problems,” analyzes Augustin. Amine Metani sums up this kinship, “what called me to Stambeli,” he explains while his colleague Ghoula mixes at a party, “is the parallel I immediately drew between an ancient ritual, a form of access to the sacred and to trance through possession, and then the club culture that I associate in a certain way with a ritual, a form of communion centered more on the figure of the DJ.” And Theophile concludes: “Stambeli has only hybridized, it crossed the desert to arrive in North Africa, and today Ammar 808 who lives in Copenhagen, makes bass music with Stambeli. Hybridization is a form of perpetuation.” In a Tunisia where identitarian tensions are resurfacing, this idea of crossbreeding and diversity embodied in these changes are beneficial. Stambeli is a fine example, and this documentary, between sacred and profane, pays it the most beautiful tribute.

Watch the entire documentary series here.

Stambeli, the spirits’ last dance (3x10min, France/Tunisia 2022)

A film by Augustin Le Gall & Théophile Pillault

An original idea by Augustin Le Gall

Produced by PAM I Pan African Music & APA : Artistes Producteurs associés

With the support of CNC Talent

© PAM & APA 2022