|

|

|||||

This week, we unpack the claims surrounding an increasingly popular renewable energy source: biofuels. They are often touted as a critical tool in the fight against climate change. But are they? Guest editor Mariam Kenza Ali from the Packard Foundation takes us on a cross-continental journey to discover the real story. |

|||||

|

|

|||||

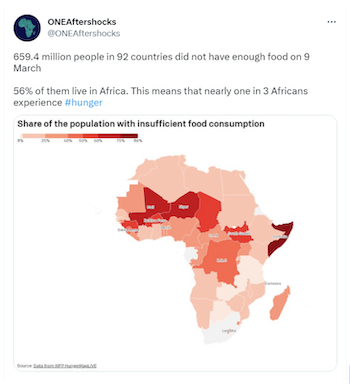

Top newsFuelling hunger: In the middle of a food crisis that’s leaving 1 in 10 people undernourished, we are burning enough food to feed 1.9 billion people to make biofuels. Biofuels use food crops, spent cooking oil, or other organic materials to create liquid fuels for transport. These fuels make up 55% of the global renewable energy mix; they make up 60% of the EU’s renewable energy. With an urgent imperative to shift away from fossil fuels, that may seem like a good thing, and the industry is expected to double by 2030. But we’ve pulled back the curtain for a look at what’s really happening... Burning calories: Biofuels are seen as a solution to renewable energy needs, but that equation may miss their impact on food security. If the US and Europe cut by half the amount of grain they burn to produce ethanol, they could fully replace all the grain exports lost as a result of the war in Ukraine. The EU burns a quantity of wheat equivalent to 15 million loaves of bread a day to make biofuels. The US converts 30%-40% of its corn and soy crops into biofuels, which drives up prices and reduces food supply. Those price hikes disproportionately impact Africa, which imports over $75 billion worth of grain annually, a significant budget hit for cash-starved governments. Food expenses account for 40% of household spending in sub-Saharan Africa, compared to 17% in advanced economies. Another not-so-fun fact: the increased production of biofuels contributed to the 2008 food price crisis.  Not all biofuels are created equal: Some biofuels are carbon neutral or even carbon negative, such as those made from waste, grasses, and fast-growing trees like eucalyptus or poplar. Those biofuels are part of the solution to climate change – but they are not the ones in widespread commercial use. Rapeseed oil and palm oil, which make up two-thirds of the EU’s biofuel sources, produce more carbon emissions than petroleum diesel. Biodiesels from vegetable oil – nearly 70% of the EU biofuel market – emit 80% more than the fossil diesel they replace. That’s before we factor in other environmental and societal impacts. Hotly debated: Even though the climate impacts of biofuels remain a contested topic, government incentives and policies are catalysing their rapid growth. Deep-pocketed lobbyists and clever marketers – benefiting from inconsistent reporting standards and monitoring and contradictory scientific findings (more on that below) – have persuaded many people, including policymakers, that all forms of biofuels are better for the planet. Reader, they aren’t. Corn ethanol enters the chat: Depending on which expert you ask, corn ethanol is BETTER! or WORSE! than fossil fuels. In one corner, serious experts assert that corn ethanol releases 46% less carbon than fossil fuels. In the other corner, expert analysis suggests that corn ethanol may emit 24% more carbon. Regardless, the US is (ahem) ploughing ahead with plans to increase corn ethanol production. The US already produces more than 40% of the world’s biofuels, and most of that is corn ethanol. Missing in this debate: the impacts of monocrop production on biodiversity and water, which are often ignored or discounted in academic analyses and public policy. 🤦🏽 Seeing the forest for the trees: Using food crops to produce biofuels at scale requires a lot of agricultural land, which inevitably means cutting down trees. That has climate consequences: the world’s forests store more carbon than all exploitable oil, gas, and coal deposits. And they absorb 30% of global annual carbon emissions – for free! Increased biofuel demand is likely to deforest an area the size of the United Arab Emirates by 2030. Africa has around one-sixth of the world’s remaining forests, and its rainforests absorb more CO2 each year than the Amazon. At current rates of deforestation, all of Africa’s primary forests will be gone by 2100. And that’s without Africa being a large producer of biofuels... yet. Going global: Despite the potential negative impacts of leading biofuels on food security and climate change, they are gaining popularity. Several African countries, including Angola, Ethiopia, Kenya, Malawi, Mozambique, Nigeria, South Africa, and Sudan, have biofuel blending mandates or targets. While Africa’s sizable arable land and electricity shortages might make biofuels seem attractive, the tradeoffs in food, water, and biodiversity security could have deadly consequences. Africa already has some of the lowest cereal yields. Sugarcane, the crop most used in African countries for biofuel, requires more water than staple crops such as sorghum and maize. One could argue that Africa’s agricultural land would be better used to produce enough food for its growing population (🚨 which is expected to nearly double by 2050 🚨). Going solar: When it comes to sustainably meeting Africa’s energy needs, solar energy offers a better value proposition than large-scale biofuel use. Solar photovoltaics can produce 100 times more energy than corn ethanol per hectare. Africa has 60% of the world’s best solar resources, but just over 1% of installed capacity. At scale, solar energy could create 3.3 million African jobs, considerably more than biofuels. If only investors would recognise what’s in front of them, and market shapers like the Credit Rating Agencies would reduce the cost of capital. Fueling hope: The link between biofuels and food insecurity is causing some policymakers to rethink their use. The EU has capped the use of food-based fuels in the transport sector at 7%. The EU also had proposed an immediate phase-out of palm and soy biofuels and, in light of the global food crisis, the EU was considering reducing the share of other crop-based biofuels by half. A provisional agreement reached on Thursday appears to have scaled back the level of ambition. While we’re still awaiting the final text, it appears there will be no phase-out of soy oil and no earlier phase-out of palm oil. The deal would, however, require that 5.5% of renewable energies for the transport sector come from non-food-based biofuels. Meanwhile, Germany is considering going even further by phasing out all food-based biofuels due to their impact on food prices and supply. 🎉 A third (and better) way: Biofuels could play an important role in helping the world achieve its climate goals. But that will require shifting to biofuels produced from waste and non-food crops that don’t cause land degradation. For the world to achieve net zero emissions by 2050 and address climate impacts on agriculture, biofuels produced from these sources should be prioritised, and land dedicated to growing food for biofuels should be rapidly re-purposed to feed 100s of millions of people. Governments have a critical role to play in prioritising food over fuel, while also incentivizing and de-risking needed investments in research and development to bring down production costs of waste and non-food crop biofuels. That will enable these more ecologically friendly biofuels to be produced at scale. Our clean energy future – and the planet’s future – may very well hang in the balance. From the ONE Team

The numbers

|

|||||

|

|

|||||

Quote of the week

|

|||||

|

|

|||||

Want to learn more?

|

|||||

|

|

|||||

|

|

|||||

The ONE Campaign’s data.one.org provides cutting edge data and analysis on the economic, political, and social changes impacting Africa. Check it out HERE. |

|||||

|

|

|||||

|

|

|||||

Did you like today's email?Loved it Mehhh Hated it |

|||||

|

|

|||||

Did you like today's email?Loved it Mehhh Hated it |

|||||

|

|

|||||

Wie hat dir dieser Newsletter gefallen?Richtig gut! Ging so… Überhaupt nicht. |

|||||

|

|

|||||

|

|||||

|

|||||

|

|||||

|

This email was sent by ONE.ORG to test@example.com. You can unsubscribe at any time. ONE Campaign |